Originally published in Wild Eye Magazine in January 2025

I never quite embraced the idea of majestic landscape photography, despite the genre’s enduring popularity and acclaim. To be clear, this isn’t to say I don’t appreciate these types of photographs. In fact, I’ve spent much of my life surrounded by landscapes that others would give anything to capture. Living a half day’s drive from Yosemite National Park and the breathtaking expanses of the Eastern Sierras, I grew up admiring the work of legends like Ansel Adams, Galen Rowell, and Brett Weston. Their imagery dominated my perception of what it meant to be a photographer, particularly one who appreciates the natural world.

The creases in this rock on Weston Beach look just like a colorful receding mountain range.

Yet, despite the beauty of these places and the mastery of these photographers, I found myself struggling to connect with that same vision. Whenever I’d reach for my 24mm lens and venture out in search of landscapes, I’d return home feeling unsatisfied with the results. Objectively, the images were solid—good compositions, balanced lighting, all the technical boxes checked—but they didn’t feel like me. They felt more like imitations, exercises in recreating someone else’s artistry rather than expressing my own vision. Over time, I began to realize that while I admired the grandeur of expansive landscapes, my creative energy was drawn elsewhere: to the minute details, the intricacies hidden within the larger scene.

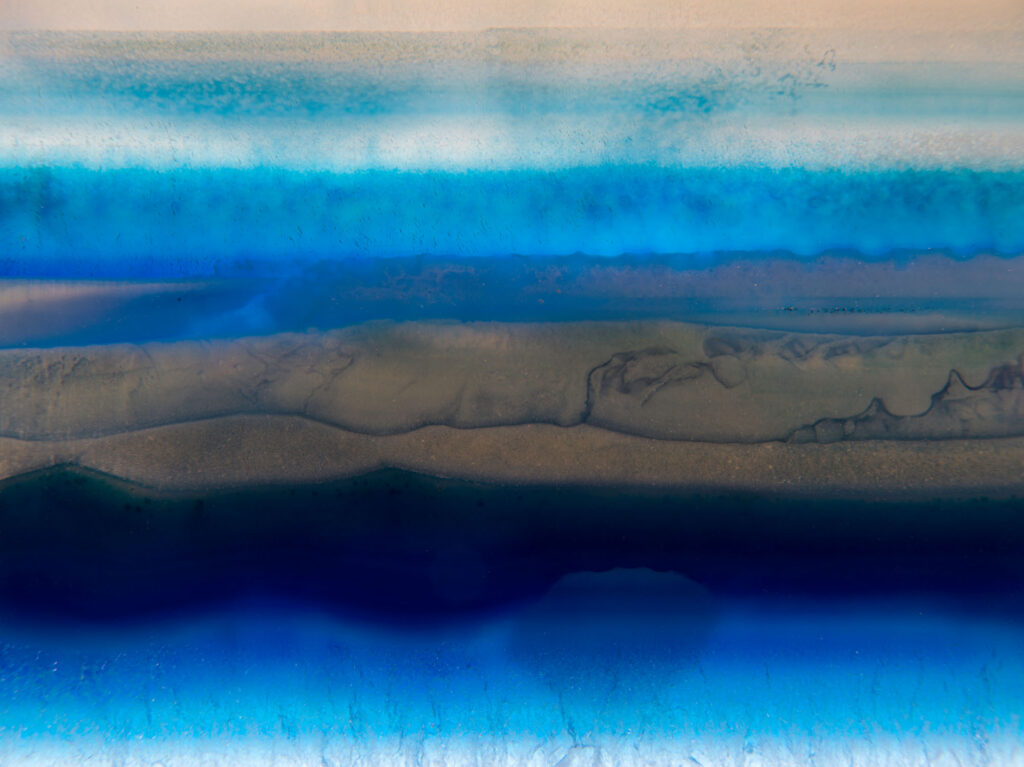

Backlighting a slice of agate and photographing it using a macro lens allowed me to create an abstract image with a painterly quality.

What I discovered was that my true inspiration wasn’t in the sweeping panoramas of mountains and valleys. Instead, it was in the subtleties that are often overlooked—the curve of a rock, the texture of a weathered surface, the way lines weave through a scene and give it structure. These small, intimate details are what stirred my imagination and made me want to reach for my camera. In this realization, I began to see myself less as a traditional landscape photographer and more as an abstract artist who uses a lens instead of a paintbrush. My work became less about capturing the vastness of nature and more about uncovering the hidden patterns and forms that give these environments their character.

Lake Magadi, Kenya, viewed from above, the cracks in this salt deposit in southern Kenya reminded me of the pattern on the side of a giraffe.

This shift in perspective was liberating. It allowed me to approach photography on my own terms and find joy in focusing on the details. When faced with a grand, awe-inspiring landscape or a charismatic animal in the wild, I didn’t feel the pressure to capture the whole scene in a single frame. Instead, I could concentrate on the nuances, on discovering tiny compositions that others might miss because they’re preoccupied with the broader view. It’s not that I deliberately avoid large compositions—it’s just that they no longer feel essential to me.

Interestingly, this approach to photography doesn’t necessarily dictate a specific lens choice, though I will admit that I have a certain fondness for longer focal lengths. The real distinction lies in how I see the world and how I compose my shots. My process always begins with a simple question: “What do I find interesting about this scene?” From there, composition becomes a matter of elimination. I systematically remove everything in the frame that doesn’t contribute to the part of the scene that captured my attention. The goal is to distill the image down to its most compelling elements, to highlight what makes it unique to me.

In Botswana’s Okavango Delta, hippos rely on their keen sense of smell to follow the exact same path each night, carving out stunning abstract patterns.

In many ways, photography has become a kind of treasure hunt for me. Take my regular walks along Weston Beach in Northern California, for example. It’s a rugged, dramatic coastline, but when I’m out there with my camera, I’m rarely photographing the broader landscape. Instead, I often find myself focused on a patch of rock no more than a few inches across. It usually starts with something small that catches my eye—a pattern of parallel lines in the stone, a crack that forms an intriguing shape, or perhaps a rock contrasting against the sand, washed up by the tide. Once I’ve found that day’s point of fascination, the real work begins. Finding the right composition is often a painstaking process, where every detail needs to fit harmoniously within the frame. Some days, no matter how hard I try, the pieces just don’t come together. But when they do—when everything aligns and I see the image clearly through my viewfinder—there’s nothing quite like that feeling. It’s as if I’ve unearthed a hidden gem, something precious that was waiting to be discovered.

Glacial meltwaters weave across southern Iceland, forming braided rivers as they flow over sediment deposits.

Not all of my treasure hunts are quite so leisurely, however. One of the most intense and rewarding experiences I’ve had as a photographer took place at Lake Magadi, which sits on the southern edge of Kenya. This body of water, with its high concentration of sodium carbonate, is an abstract photographer’s dream. When the conditions are right, the lake’s surface transforms into a shifting mosaic of colors and patterns, driven by the interplay of wind, algae, and changing temperatures. But capturing these patterns isn’t as simple as walking up to the shore with a camera in hand. To get the shots I wanted, I had to charter a helicopter—a thrilling, but expensive, endeavor. With limited time in the air, I had to make the most of every moment, which added a level of pressure and intensity that I don’t usually experience.

In situations like this, preparation becomes just as important as artistic vision. Before heading out to Lake Magadi, I spent hours researching the area and looking at other photographers’ work to get a sense of what I didn’t want to do. As I scrolled through photos, I saw plenty of striking images—elegant swirls of algae, flocks of flamingos reflected in dark water—but none of them felt right for me. I wasn’t interested in creating images that echoed what had already been done. What I wanted were bold, frame-filling blocks of color, defined by distinct patterns and shapes. Flamingos might be a nice addition to the composition, but only if they felt essential, not ornamental. This clarity of purpose allowed me to focus my efforts during the brief time I had in the helicopter, helping me capture the images that aligned with my vision.

Sometimes the pattern you’re chasing isn’t fixed in place. In fact, there are times when you have to physically chase it—because it happens to be attached to a zebra. Not just any zebra, but a Grevy’s zebra, with its unusually fine, intricate forehead stripes. For hours, I found myself searching for the perfect zebra, one whose head would align in just the right way to match the narrow depth of field I needed with my 600mm lens. My guide thought I was completely out of my mind, but I was determined. And when I finally captured that moment, with everything in harmony—the patterns, the stripes, the precise composition—I returned home absolutely elated.

As the final rays of the setting sun bounced around the curves on the roof of an ice cave, the ice took on the look of molten metal.

The pursuit of patterns has often led me to places where most would question the sanity—or at least the practicality—of my decisions. One such journey took me deep into an ice cave in Svalbard, accessible only by a roped descent into the frozen underworld. The goal? To capture an intricate ice formation that resembled a frozen fragment of Earth’s internal plumbing, with its twisting shapes and translucent curves. Just like in my other work, this shoot became an exercise in elimination. The sub-glacial structure towered 20 feet high, but I wasn’t interested in the entire mass. Instead, after a meticulous search, I honed in on a tiny section—one small area that not only stood out graphically but also, to me, seemed to encapsulate the essence of the entire cave.

In the end, whether I’m photographing a stretch of rocky coastline or flying over a remote lake in Africa, my approach remains consistent. I’m always searching for the hidden details, the elements that others might overlook in their pursuit of the grander scene. Photography, for me, is about distillation—stripping away the unnecessary until only the essence remains. It’s a process that requires patience, a willingness to experiment, and, above all, a deep appreciation for the small wonders that make up the natural world.